Adam Shaw, Sound Designer

Hey folks. My name is Adam Shaw and I’m the sound designer at Simutronics. How did I get such a sweet job? Well, I originally studied music with the intention of getting into studio engineering, but the more I did it I realized I wasn’t nearly as passionate about the music as I was about the technical processes involved in mixing and mastering audio. I got involved with Simutronics as a QA intern and quickly realized that sound design was an area that I could really contribute to.

What does this sound like?

Our current project, Dragons of Elanthia, is really fun and challenging to work on. Considering we have an ever-expanding cast of dragons and riders, and some really dynamic environments with a life and personality of their own, there’s never a shortage of creative work to do. My favorite part of all this is the voice-overs. When we’re doing voice-work, our recording sessions can be a lot of fun and typically result in someone laughing until they cry. Audio work isn’t without obstacles though. One of the biggest challenges I’ve encountered while working on this game is trying to properly attenuate all of the sounds in a 3D environment to sound realistic while our dragons fly past each other at breakneck speeds. Making sure players can get a good feel for how far away something is can be a daunting task even with the powerful tools and plug-ins we use. Feedback is everything and making sure our players know what’s coming at them and where it’s coming from is a difficult but rewarding endeavor.

What does this sound like?

So how do we get from idea to implementation? The process isn’t always a clear progression from A to Z, but it generally looks a little bit like this:

Typically the need for a particular sound starts with design. For example, “Hey, we’re going to make a Lich rider that collects souls from his fallen enemies and allies and uses those souls as projectiles.” Even without knowing what this effect is going to look like I get a few pretty good ideas for how this ability needs to be characterized. Here’s what I know: The rider is undead, these projectiles are disembodied dead, and I need a few different sounds, one for collecting souls, one for firing them, a loop for the projectiles in flight, and one for when the projectiles collide with the environment or another player. This gives me a pretty good baseline to start concepting and collecting source material.

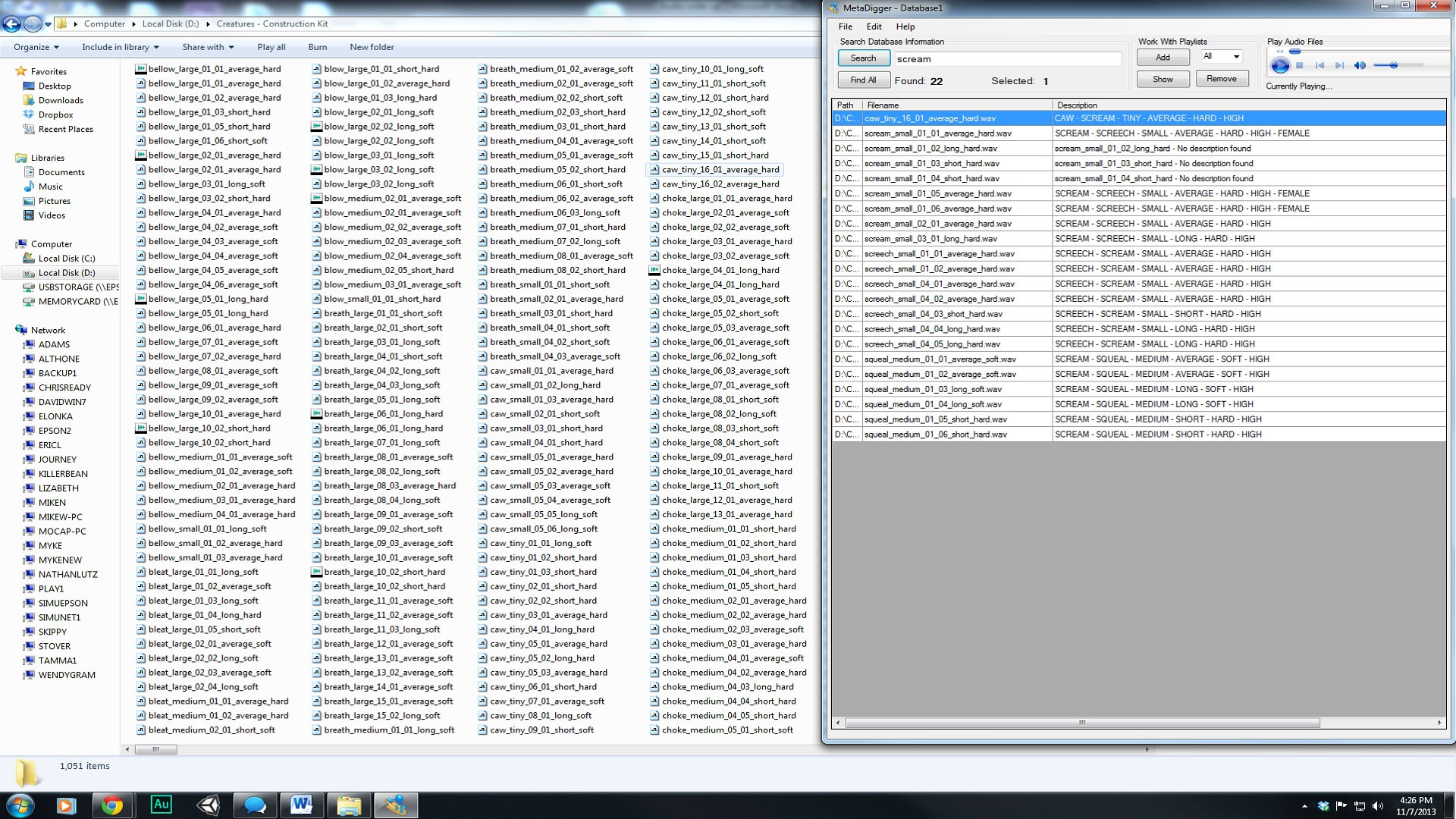

Collecting source material takes one or two forms (maybe both). The first is checking our sound libraries for relevant material. Maybe we have a dark magic library, or maybe I recorded someone screaming like a banshee for a previous project. Most of our audio files are tagged with relevant metadata so they can be searched for quickly. I use a tool called metadigger to scour through our libraries for things using keywords like "dark," "scream," or "soul."

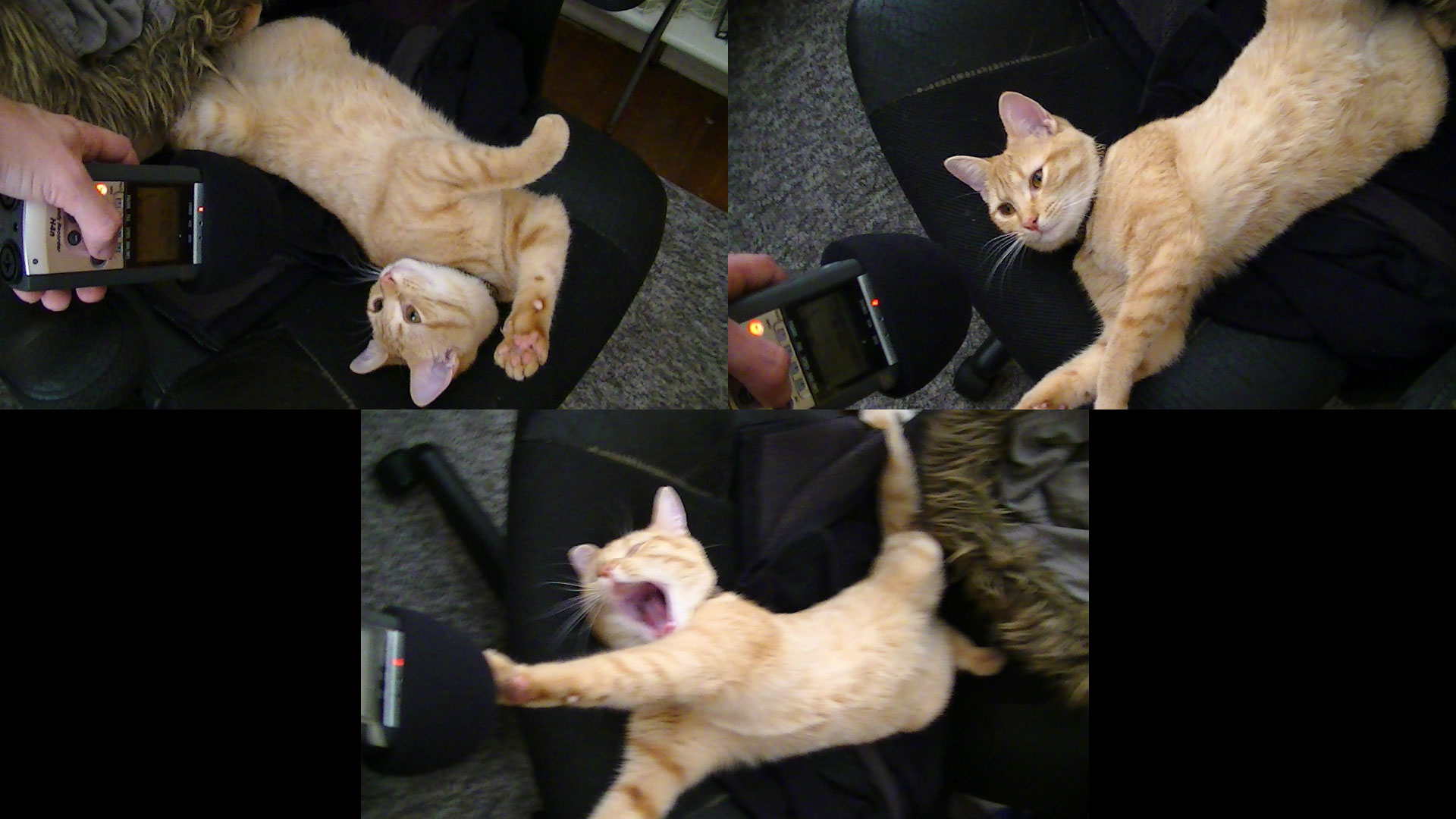

If the sound libraries come up empty, it’s time to put on our work pants and record it ourselves. I do most of my field-work with a Zoom H4n portable recorder and either an Audix SCX1 hypercardioid condenser or an Azden SGM-1X shotgun condenser. When you’re recording your own sounds it’s important to remember that your source material may not always match the final sound you want… in fact it frequently won’t! Recording dragons is its own kind of challenge; they have impossibly busy schedules and if you stress them out too much they have a nasty habit of incinerating the microphones, so I prefer using less temperamental animals for my source audio… animals like this one:

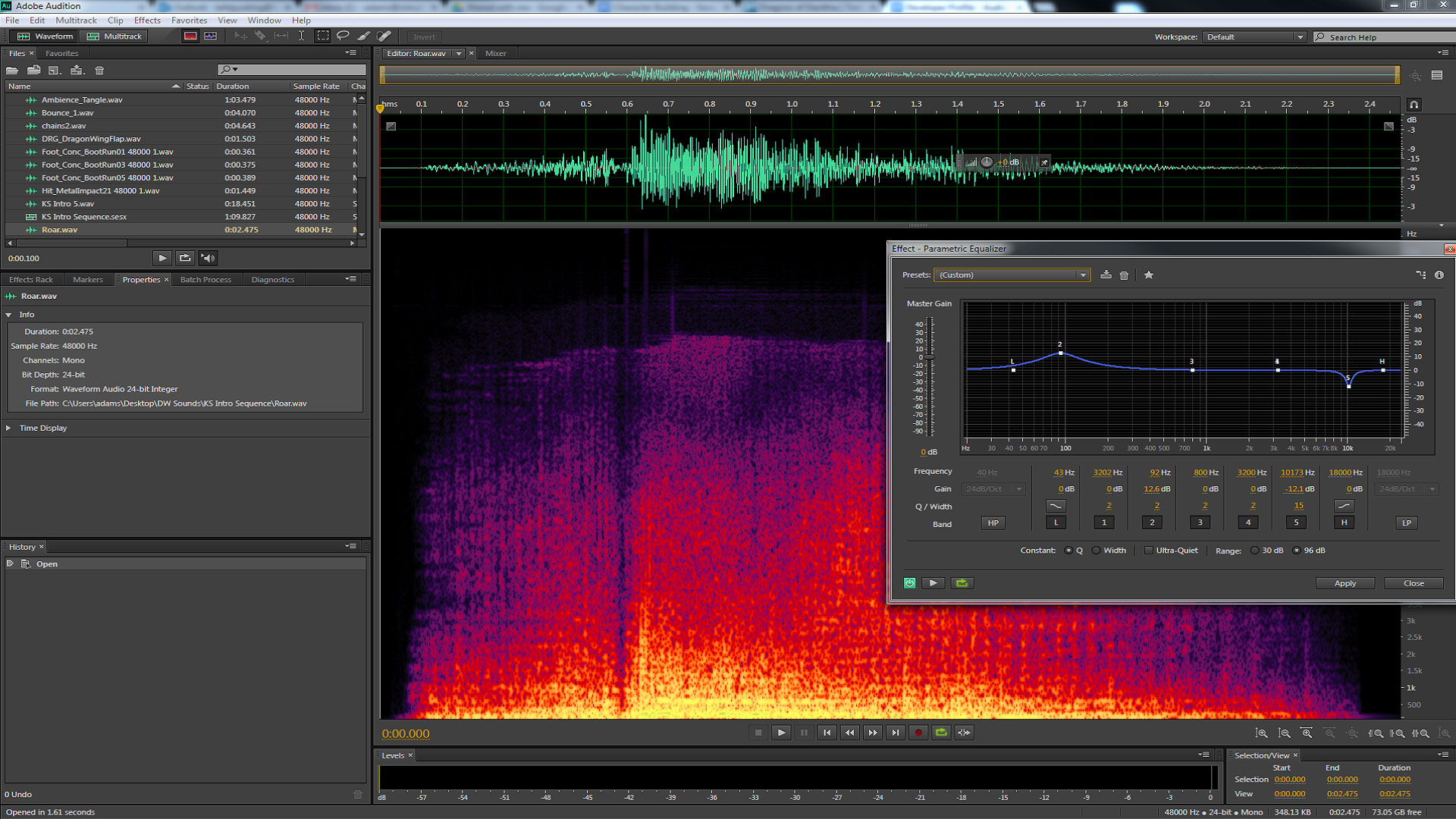

After I’ve collected my source materials it’s time to get into post-production. This is where all the digital magic happens. EQ, compression, pitch manipulation, and any other effects are applied at this point. There’s a lot that goes into this step that I could get into, but there are resources all over the net that explain this process way better than I ever could. I personally use Adobe Audition CC as my audio workstation but there are a number of other great programs you can use.

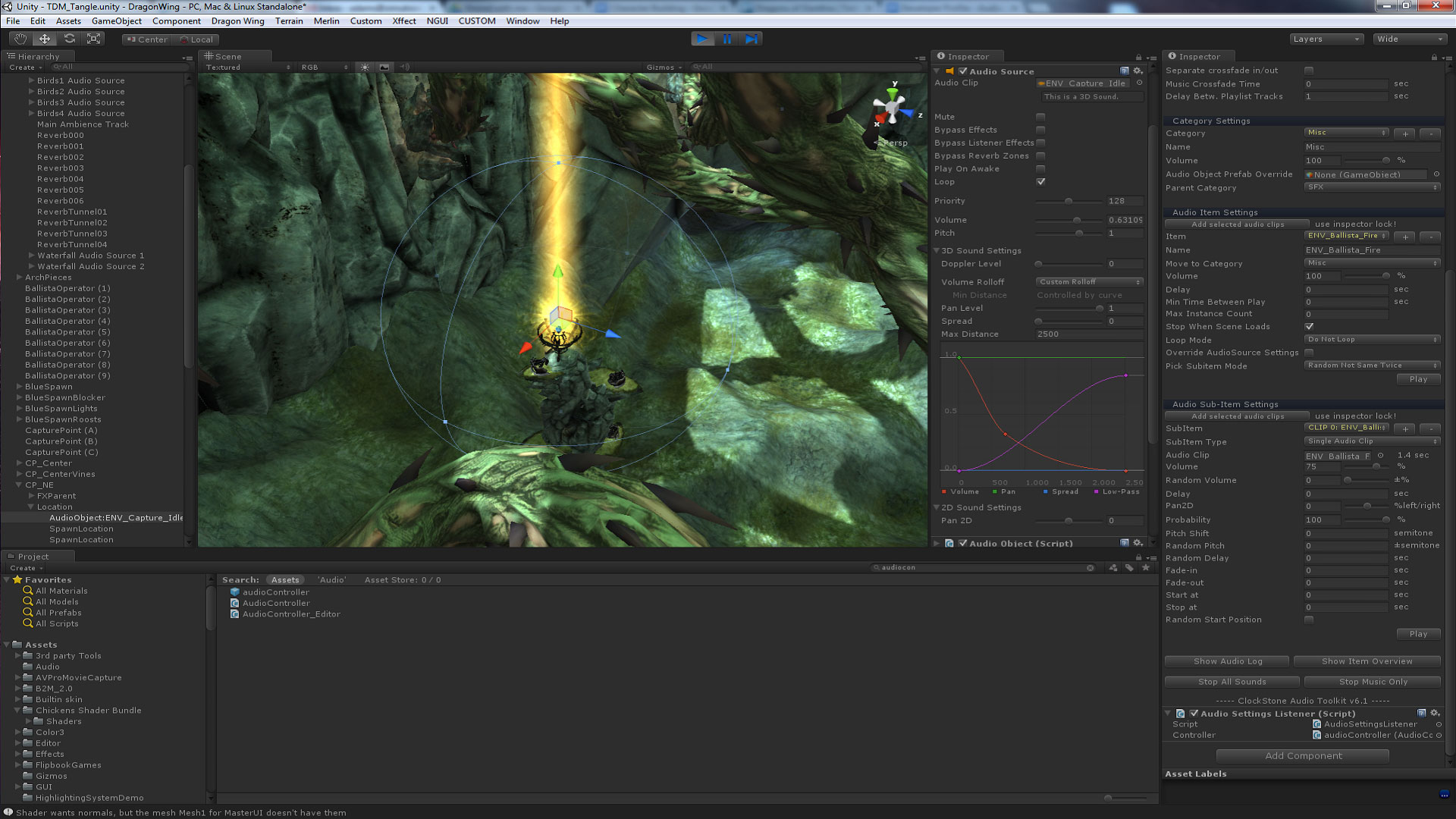

At this point the workflow gets a little bit fuzzy. If the effects for the ability I’m working on are already in the game, I can implement the audio into the project and see how it matches up with the effect. If the effects aren’t already in the game, I’ll start a dialogue with the technical artist(s) and try to get a feel for what the effect will look like so I can make adjustments to the audio while I wait for the effects to be finished.

Implementing the audio into the project is fairly straightforward but also requires as much or more finesse than production. Attenuating the sounds in the 3D environment is a delicate balancing act that can leave the player completely overwhelmed if there’s too much feedback or totally lost if there’s not enough.

Once the audio is actually implemented in the game it’s time to play—I mean test—I mean… play-test. Making audio in a video game is a lot like being a ninja; the goal at this point is to go completely unnoticed. If someone is flying around and shooting their friends and goes "Wait … what was that? What did I just hear?" I have failed as a ninja. I actually think one of the best compliments someone can give a sound designer is "Wow, that environment felt really alive … I don’t really know why." If my presence as a sound designer is detected in the game, it’s back to the drawing board.

Thanks for swinging by and feel free to ask me questions in the comments.

Adam "Typo" Shaw